In early 2025, Evelina and Guillaume, a Parisian couple, were getting ready to become parents for the first time. The pregnancy had been smooth: the baby had a strong heartbeat, was growing well and kicking often. So when they showed up for their second-trimester ultrasound, they were full of excitement, mostly to find out the baby’s gender.

It was a girl. The midwife shared the news early in the appointment, setting a pleasant mood in the room. But soon after, that mood shifted. "This is unusual," he said. Something about the baby's spine didn’t look right. Evelina and Guillaume left the scan holding a document that read: “Suspicion of spina bifida; further scans required.”

Several appointments later, the diagnosis was confirmed. Their daughter had spina bifida—a serious condition that neither of them had heard of before.

More common than you’d think

They are far from being alone. In France, spina bifida affects almost 1 in 1,000 pregnancies. Worldwide, an estimated 51,000 babies are born with it every year. It’s a fetal anomaly that happens very early in pregnancy, sometimes before a woman even knows she’s pregnant.

Spina bifida affects thousands of newborns worldwide

Prevalence per 10,000 births for a selection of countries where recent data is available

Source: ICBDSR Report, 2024. For countries where multiple values are available, the highest one is shown.

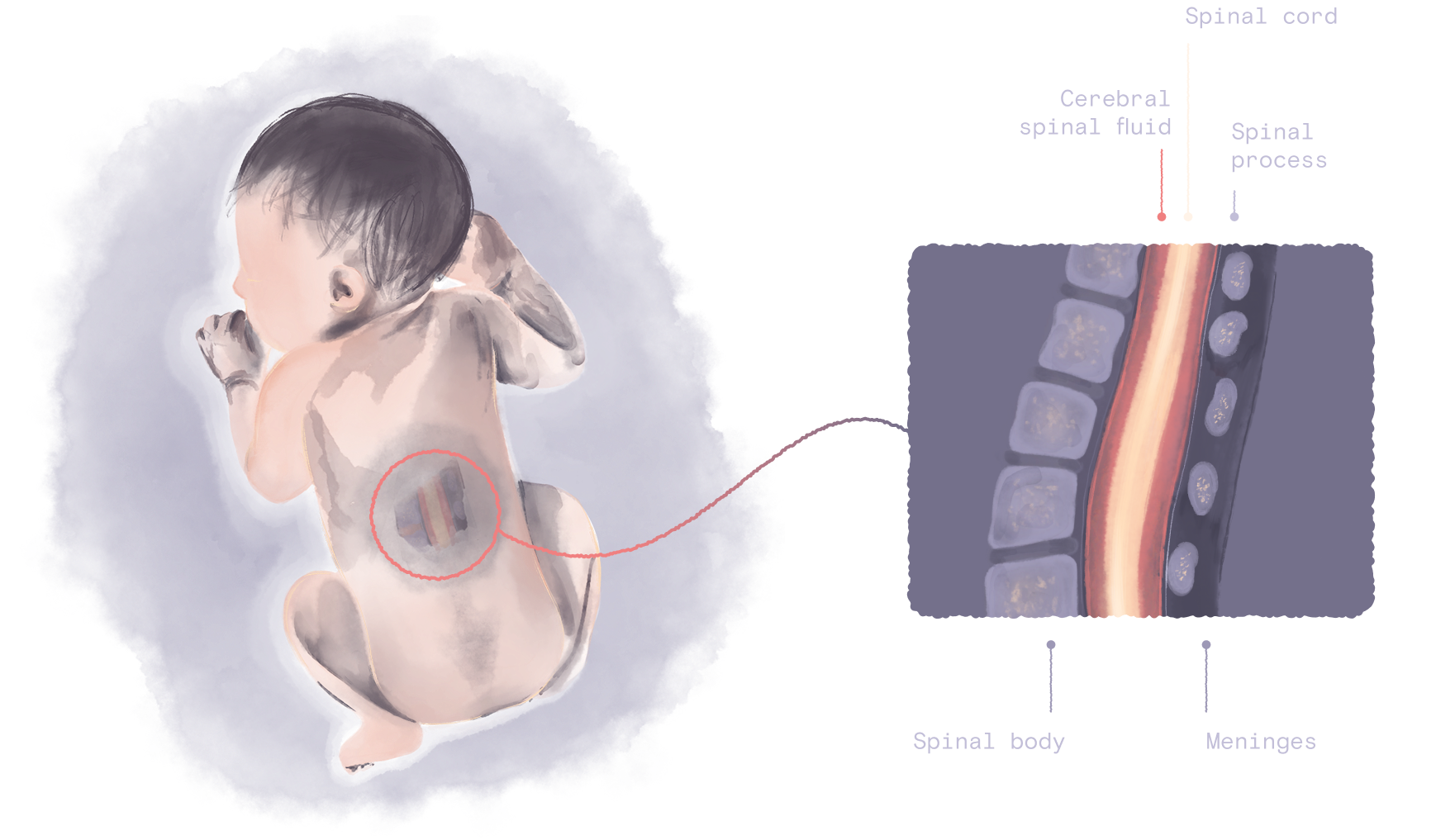

How does it happen? Around the third or fourth week after conception, a structure called the neural tube is supposed to close—like a zipper sealing up along the baby’s back. This tube later forms the brain and spinal cord. But in some cases, it doesn’t close properly, causing a neural tube defect (NTD). Spina bifida is a type of defect that occurs at the lower end of the tube, leaving part of the spine exposed.

Normal spine

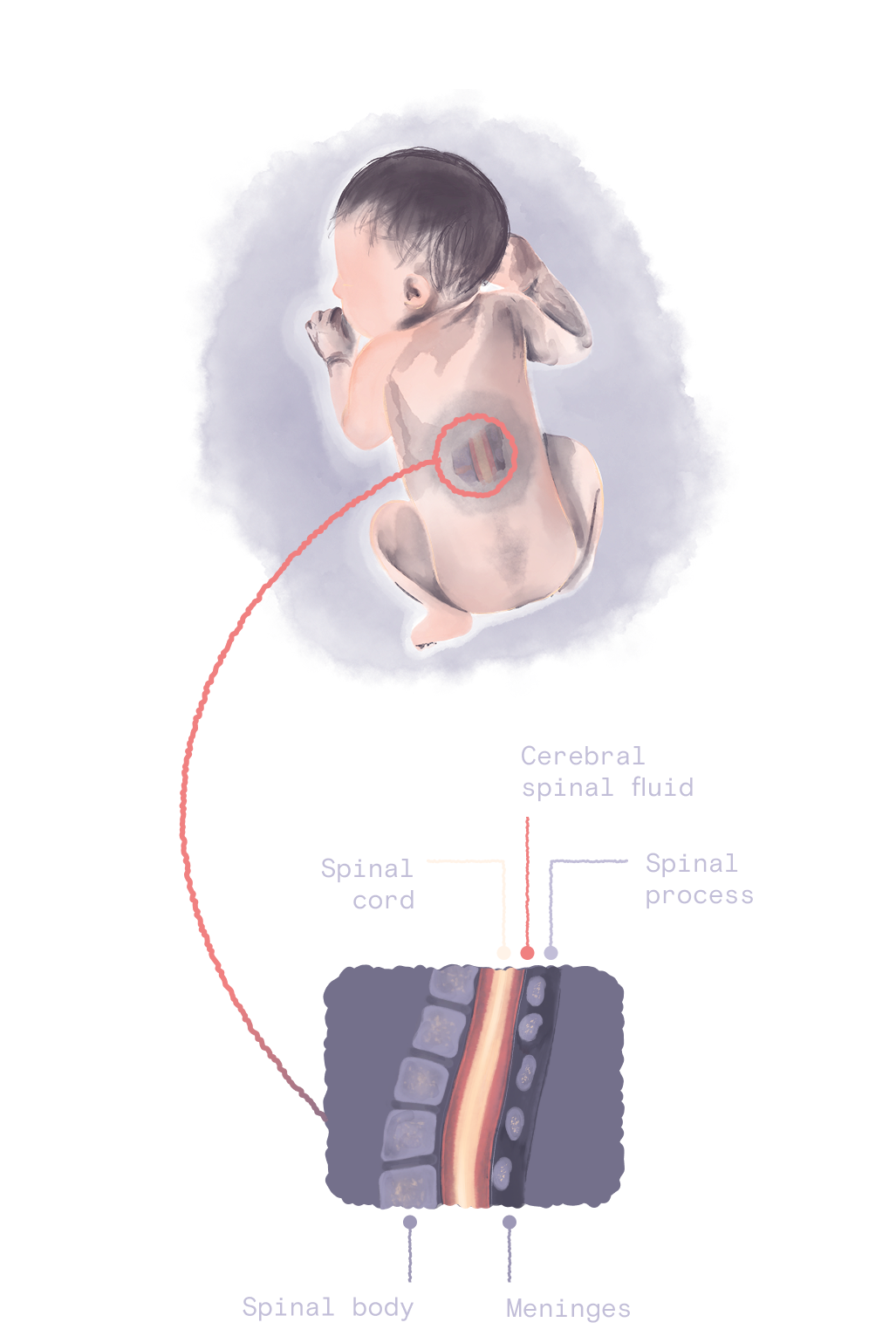

There are different types of spina bifida, typically grouped as either closed or open defects. The mildest, spina bifida occulta, is hidden under the skin. Many people with it go their whole lives without knowing: it causes no symptoms and is often discovered by chance.

But in about 90% of diagnosed cases, the defect is open—meaning part of the spinal cord or its protective membranes push through the baby's back. One type is meningocele, where a sac of fluid pushes through the spine. The most severe form though is myelomeningocele, where both nerves and spinal tissue are exposed in a sac on the baby’s back. Evelina and Guillaume’s daughter had this most severe form.

Closed spina bifida

Small gap in the spine, no sac or protrusion

Closed spina bifida

Sac of cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF) protrudes

through the back

Sac contains

both CSF and spinal

cord or nerves, which are often exposed

Closed spina bifida

Open spina bifida

Note: Other rarer, skin-covered forms of spina bifida exist but are not shown here.

The silent consequences

Have you ever heard of this anomaly? Probably not. Spina bifida isn’t often talked about and there’s a reason for that. In countries where prenatal screening is standard, neural tube defects are typically detected during the second-trimester scan, around the halfway point of a pregnancy. From there, parents face a decision: continue the pregnancy or choose to terminate, if the laws allow. Many choose the latter. As a result, a large proportion of babies diagnosed with spina bifida never make it to a live birth.

Termination is a common outcome after diagnosis

Median termination prevalence in Europe following prenatal spina bifida detection

Source: European Platform on Rare Diseases Registration, 2023. Confidence interval ranges from 55% to 71%.

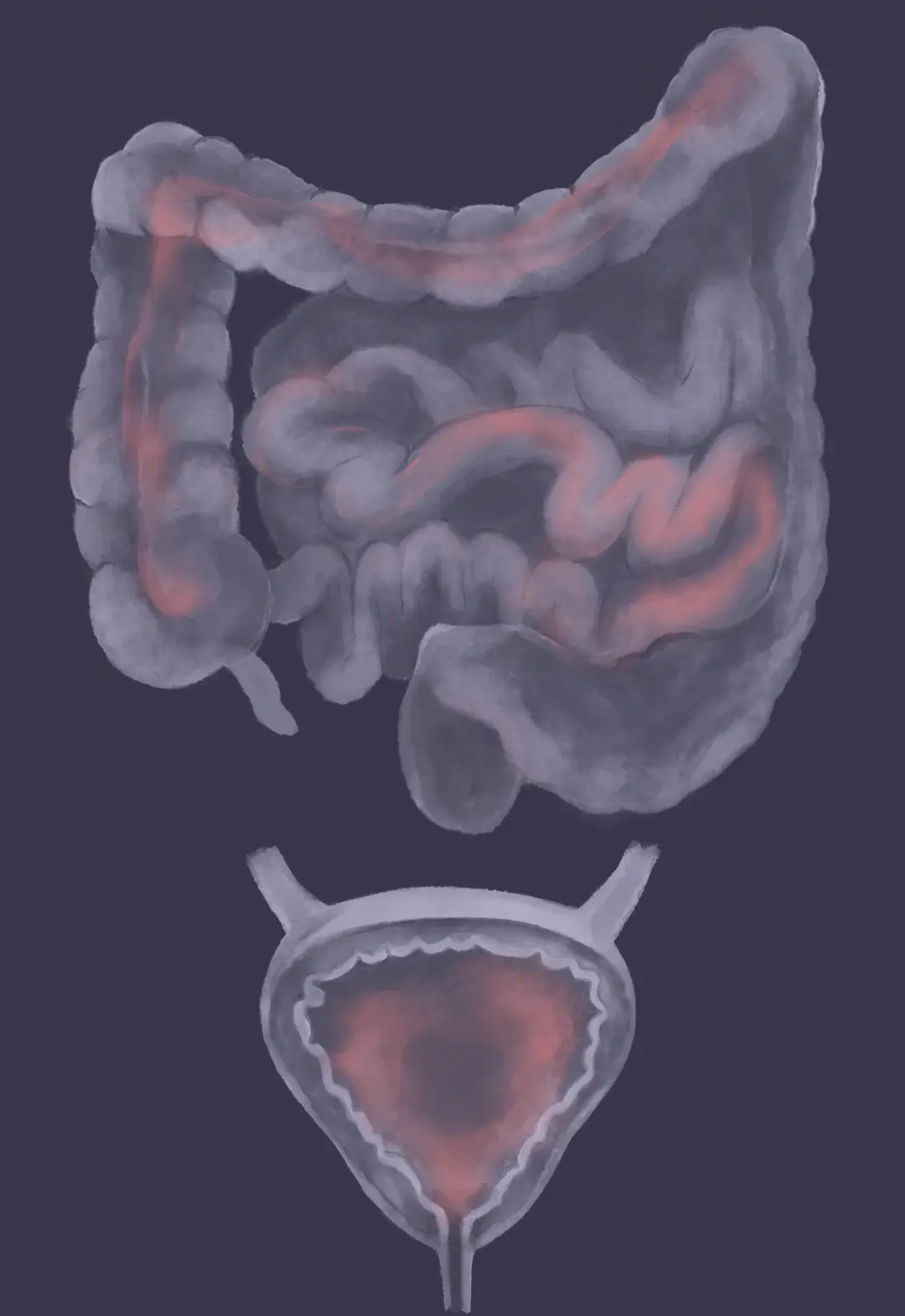

That’s the decision Evelina and Guillaume came to, after consulting with some of the best fetal and pediatric surgeons in France. In their daughter’s case, the opening in her spine was low, in the sacral region—guaranteeing life-long issues with bladder and bowel control and an uncertain chance of walking. On June 18, 2025, at 26 weeks of pregnancy, they chose to let her go. Having to make that call was heartbreaking for them and is for all other parents facing the same diagnosis.

Meningocele effects

Myelomeningocele effects

Evelina and Guillaume’s decision reflects one possible path. For those who decide to continue the pregnancy, prenatal surgery can sometimes be considered to partially repair the lesion before birth. This procedure remains rare, as eligibility criteria are very strict and it carries significant risks such as preterm labour and, less commonly, uterine rupture.

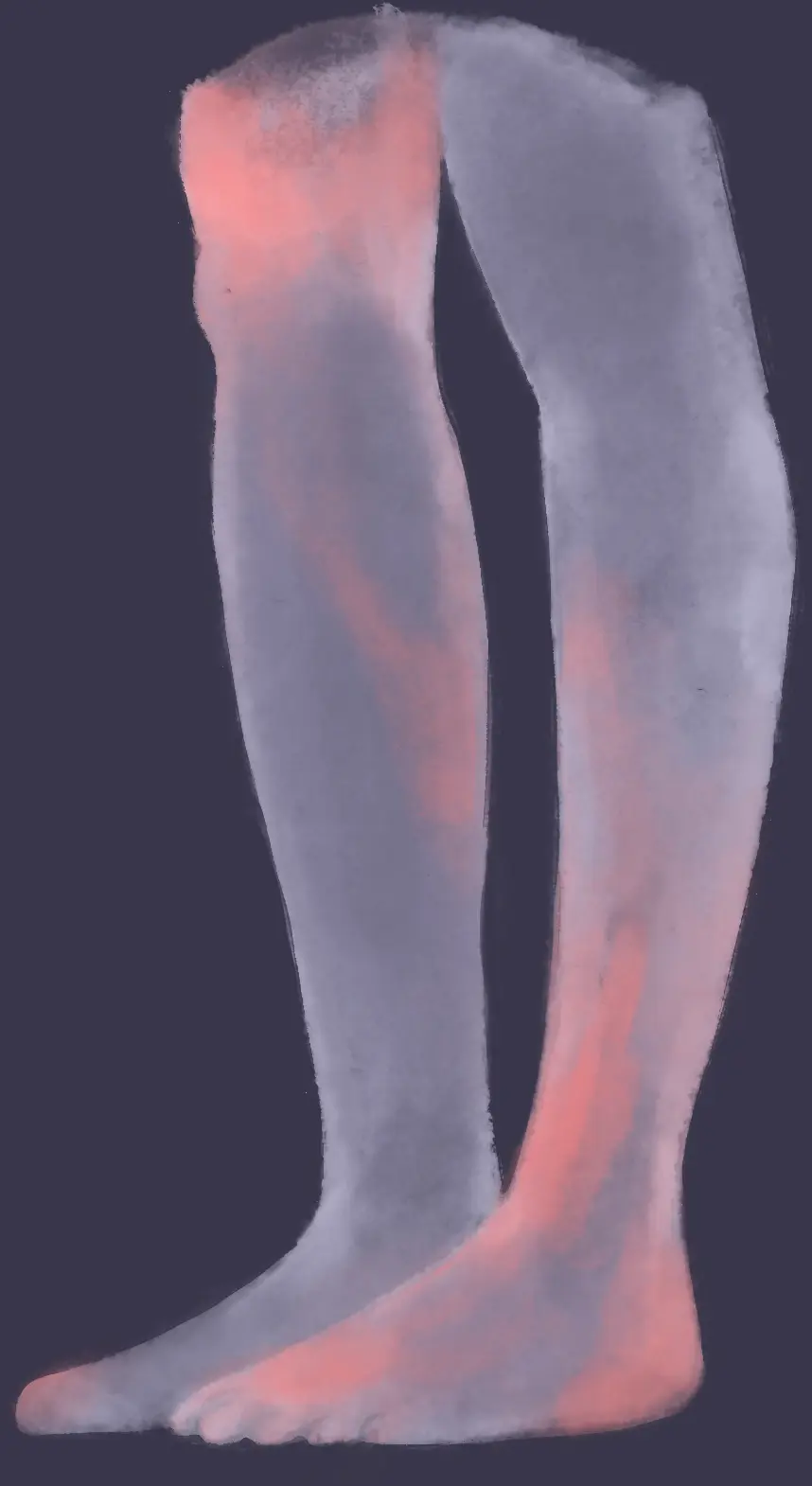

When the pregnancy continues to term, the data—though limited—offers a glimpse into what life with severe spina bifida often looks like. In the US, around 6 in 10 children with myelomeningocele are unable to walk independently. Almost 70% live with ongoing bowel and bladder difficulties. Many undergo multiple surgeries and require lifelong support. Similar outcomes have been reported across Europe and beyond.

People affected by spina bifida also face social and emotional challenges. As kids, they are more likely to struggle with self-esteem, depression and making friends. The difficulties often carry into adulthood, where navigating independence becomes another uphill battle.

Spina bifida affects key aspects of physical life

Disabilities faced by those living with open spina bifida

Source: CDC Findings from the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry, 2022. Based on a CDC registry of 8,000-11,000 participants.

It goes without saying that spina bifida is not a diagnosis any parent hopes to receive. The choices that follow are deeply personal and painful. Some families decide to continue the pregnancy, knowing it will likely mean a lifetime of surgeries, disability and uncertainty. Others choose to terminate. Because neural tube defects are usually detected around mid-pregnancy, termination at that stage involves going through labour and delivery—an experience that can carry lifelong emotional scars. So is there a way to reduce the risk of the anomaly altogether?

A condition we can help prevent

Spina bifida has many causes—ranging from genetic factors, such as a family history of neural tube defects, to environmental influences like maternal diabetes or obesity. Certain medications, especially anti-seizure drugs, have also been linked to higher risk. But one of the most important and well-understood factors that affects everyone is folic acid, also known as vitamin B9.

This essential nutrient plays a key role in DNA synthesis and cell division, enabling the rapid growth needed for the neural tube to form and seal correctly. A lack of it during the critical early weeks of pregnancy significantly increases the risk of a neural tube defect. Studies show that, when taken before and during the first trimester of pregnancy, folic acid can prevent up to 70% of neural tube defects.

Since this research has become public, health authorities started recommending folic acid supplements for anyone who could become pregnant. Many countries responded by fortifying staple foods with it: in the U.S. and Canada, for example, vitamin B9 has been added to flour and cereals since the late 1990s.

Less than half of the world’s countries fortify cereal grain with folic acid

Countries that fortify at least one grain—wheat, rice or maize—with vitamin B9

.svg)

Source: Food Fortification Initiative, 2023

Has fortification been helpful? Absolutely. A review of 75 countries found that populations with mandatory folic acid fortification had roughly half the rate of neural tube defects compared to those with none. This has been observed not only in high-income but also in low- and middle-income countries. Costa Rica ran a folic acid food fortification monitoring programme between 2010 and 2020 which confirmed a 53% decrease in the prevalence of NTDs.

Mandatory fortification has been proven to work

Prevalence of neural tube defects per 10,000 births in countries with and without fortification

Source: Global heterogeneity in folic acid fortification policies and implications for prevention of neural tube defects and stroke, 2023

Of course, folic acid isn’t a cure-all. Evelina took supplements for a few months before getting pregnant, yet her baby's neural tube didn't seal as expected. But the science is clear: fortification helps prevent spina bifida and other neural tube defects. Despite this knowledge, most European countries—including France—have not yet adopted mandatory fortification, impacting thousands of pregnancies each year.

Had folic acid fortification been implemented in EU member states in 1998 (at the same time as the US), an estimated 19,500 neural tube defects could have been prevented as of 2021.

Source: Eurocat

What you can do

Until we know more, folic acid remains our most powerful form of prevention. Here’s how you can help bridge the prevention gap today.

If you’re planning to have children, start taking folic acid a few months before trying. Consult your OB or pharmacist for the dosage.

If you’re in healthcare, make sure your patients understand the importance of taking folic acid before and during pregnancy.

If you’re in government or public health, support policies that make folic acid available through food fortification.

Have a story to share?

Has your baby been diagnosed with spina bifida? Consider sharing your experience with us. We’ll feature it on this page to raise awareness together.

Approach

We've simplified the science of spina bifida to make this article accessible to everyone. Some concepts are hence not covered—rarer spina bifida types and folate metabolism. To learn more, refer to the research papers linked throughout this article.

Acknowledgements

Evelina and Guillaume would like to express their gratitude to the fetal medicine and obstetric teams at Hôpital Armand-Trousseau who guided them through this difficult journey with incredible kindness and professionalism.